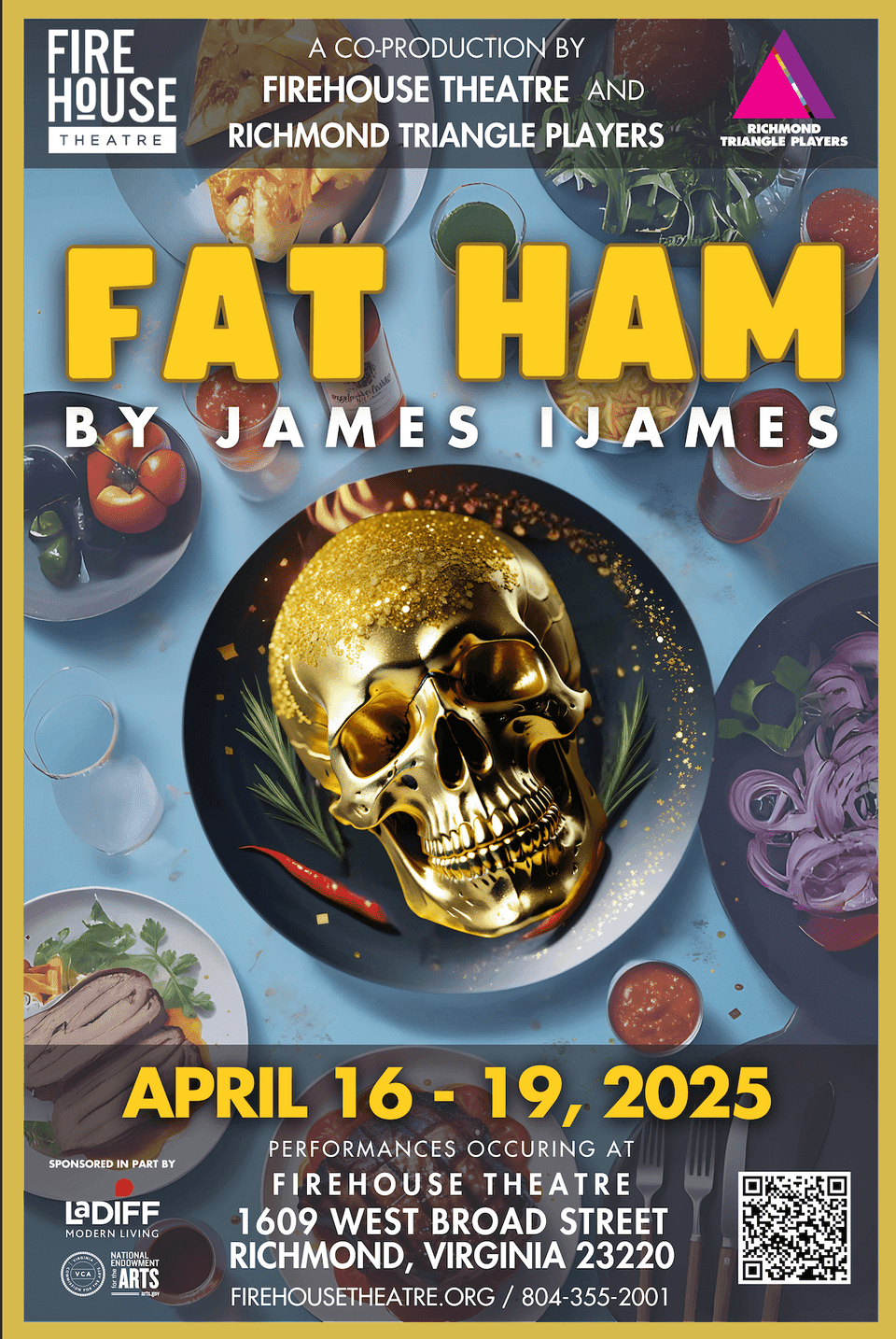

A Co-Production of Firehouse Theatre and Richmond Triangle Players

A Reflection on a Unique Theater Experience by Julinda D Lewis

At: Firehouse Theatre, 1609 W Broad St., RVA 23220

Performances: April 16-19, 2025

Ticket Prices: $45 [all shows SOLD OUT]

Info: (804) 355-2001 or firehousetheatre.org

Fat Ham is what happens when Shakespeare gets invited to the BBQ and there’s brown liquor and the Electric Slide – the only thing missing is a game of Spades.

What is Fat Ham? James Ijames’ 2022 Pulitzer prize winning play is a modern-day take on Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Set in a small town in North Carolina (or Virginia, or Maryland, or Tennessee), Juicy’s father, Pap, has died and his mother, Tedra, immediately married her deceased husband’s brother, Rev. Mere moments into the contemporary tragedy (or tragi-comedy), Pap appears to Juicy and his friend Tio as a ghost. As if to make sure we get the “comedy” part of tragi-comedy, Pap has thrown a large white sheet, complete with pasted on black eyeballs, over his pristine white funeral suit and strolls into the backyard using the gate. I’m not the only one who wondered why he didn’t just walk through the fence, as his son, Juicy also asked why he wasn’t floating! Point made, he subsequently ditches the sheet and appears in his white suite with a wide-brimmed white hat and white shoes.

Named in honor of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and the BBQ restaurant owned by the play’s fictional family, Fat Ham is equal parts family tragedy and side-splitting comedy. Pap has roused himself from the grave to ask his son to seek revenge. Apparently, while in prison serving a sentence for stabbing a man, he himself became the target of a hitman when his own brother, Rev, has him killed. The plot thickens when Pap, Rev, and just about every other adult in his life questions Juicy for being “soft,” calling him a sissy and other choice names.

As the drama unfolds, two of Juicy’s friends come – or get forced out – of the closet. Tedra’s conflict is also internal as she faces her own insecurities that make her think she can find her worth only in the arms of man. Criticism is met with a variety of explanations, all ending with, “it’s biblical” or “it’s in the bible.”

There was plenty of drama off the stage as well. After a successful run in Norfolk earlier in the year, Virginia Rep was set to bring Fat Ham to the November Theatre but cancelled at the last minute due to their on-going financial problems that surfaced for the public in the fall of 2024. While it may be true that finances were the source of the cancellation, the optics were not good. Fat Ham is very much a Black and Queer play, and with all the controversy over Black History Month, DEI, and the like, well feelings were ruffled.

In what was a huge surprise to many if not most of us (the RVA theater community), the Firehouse Theatre, under the direction of Producing Artistic Director Nathaniel Shaw and Richmond Triangle Players, where Philip Crosby is Executive Director, joined together to co-produce Fat Ham with the same Norfolk cast that was originally expected to bring this production to the River City. The five performances were fully sold out before most of the general public even heard about the event. So, for many reasons, Fat Ham is not just any play, this was not just any production, and I felt blessed to secure a seat.

Bringing this show to life, complete with physical comedy, amazing soliloquys, some of which reference Shakespeare and some of which are taken verbatim from the bard’s Hamlet – such as “what a piece of work is a man” – is a dynamic cast consisting of Marcus Antonio as Juicy/Hamlet, Kevin Craig West as Pap/the ghost of Hamlet’s father and Rev/Claudius, Cloteal L. Horne as Tedra/Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, and Adam E. Moskowitz as Juicy’s/Hamlet’s sidekick Tio/Horatio. Notice the pattern that is beginning to emerge? Jordan Pearson plays Larry/Laertes, Janae Thompson is his sister Opal/Ophelia, and Candice Heidelberg is their mother Rabby/Polonius.

Antonio is alternately sly, soft, philosophical, and just generally endearing as Juicy (although I had a hard time swallowing that name, LOL). Horne is so over-the-top as his mother, Tedra, that the moments when she is serious are all the more powerful. She stands up for Juicy, refusing to allow Rev to spread his homophobic poison and at the same time, like most of the Black mothers I grew up in community with, was very protective of her son while maintaining a boundary that defined how people defined her and her life choices.

Jordan Pearson was a supporting character who came later on the scene but made a huge impact, transforming from a straight-edged marine to puffed sleeves, feathers, and a metallic gold head piece. Moskowitz – who reminded me more than once of a version of Spike Lee, perhaps from Do the Right Thing – shared a bizarre sexual fantasy involving a gingerbread man, a snowball fight, and fellatio that had his character questioning the origins of his weed. It was the kind of story, a confession, that one has to blame on the weed, or on alcohol, in order to be able to hold one’s head up in public ever again!

Another memorable scene Moskowitz shared with Antonio involved Juicy asking his friend Tio about his shoes. This gives rise to another direct Shakespearean reference, “You remember Yurick?” It seems Yurick (who was not give a contemporary name) was Juicy and Tio dead friend, and Tio bought Yurick’s shoe at a yard sale being held to raise money for Yurick’s funeral.

Thompson’s Opal, unlike Ophelia, does not end in death by drowning – or any other means – but, rather, with affirmation and freedom. While her brother, Larry/Laertes, is not happy with the military life he is living to please his mother, Opal longs for it – it would provide her freedom she does not currently have as a woman, as a Black woman, as a Queer Black woman.

West, who played the unlikeable brothers Pap (God doesn’t want him and the devil won’t have him) and Rev (a blend of charming yet controlling as are most narcissists), redeemed himself – in the eyes of the audience and his fellow cast member – with a shocking and hilarious death scene.

Unlike a Shakespearean tragedy that ends with most of the main characters dead and strewn about the stage, Fat Ham ends with the cast breaking out in dance. (I believe the script may have originally called for a disco ball to descend at this point.) With the suddenness of this production’s manifestation, and the fun-size stage at Firehouse, it was not possible to transport the stage used in Norfolk, so Firehouse staff constructed a new set in 48 hours!

There is tragedy. There is the angst of young people seeking purpose. There’s the dysfunction that results from the machinations of adults trying to make the best of a difficult situation, the burdens society expects them to carry, and the weight of tragedy. There is also humor and an earnest attempt to make the best of whatever life throws at you. As Tio says, “Why be miserable trying to make somebody else happy?”

—–

Julinda D. Lewis is a dancer, teacher, and writer who was born in Brooklyn, NY and now lives in Eastern Henrico County. When not writing about theater, she teaches dance history at VCU and low impact dance fitness classes to seasoned movers like herself and occasionally performs.

—–

FAT HAM

Written by James Ijames

Directed by Jerrell L. Henderson

CAST

Marcus Antonio ….. Juicy

Candice Heidelberg ….. Rabby

Cloteal L. Horne ….. Tedra

Adam E. Moskowitz ….. Tio

Jordan Pearson ….. Larry

Janae Thompson ….. Opal

Kevin Craig West ….. Pop/Rev

CREATIVE TEAM

Jerrell L. Henderson ….. Director

James Ijames ….. Playwright

Nia Safarr Banks ….. Costume Designer

Caitlin McLeod ….. Scenic Designer

Jason Lynch ….. Lighting Designer

Sartje Pickett ….. Sound Designer

Kim Fuller ….. Production State Manager

Performance Schedule:

Wednesday, April 16, 2025 7:30PM Opening Night

Thursday, April 17, 2025 7:30PM

Friday, April 18, 2025 7:30PM

Saturday, April 19, 2025 2:00PM

Saturday, April 19, 2025 7:30PM Closing Performance

Run Time: about 1 hour 45 minutes with no intermission

Photo Credit: Photos on Firehouse & Richmond Triangle Players Facebook pages by Erica Johnson @majerlycreative

Adam E Moskowitz

Make a one-time, monthly, or annual donation to support rvart review

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly